John Alexander McCrae

Posted on August 2, 2014 Leave a Comment

Lieutenant Colonel John Alexander McCrae, MD (November 30, 1872 – January 28, 1918) was a Canadian poet, physician, author, artist and soldier during World War I, and a surgeon during the Second Battle of Ypres, in Belgium. He is best known for writing the famous war memorial poem “In Flanders Fields“. McCrae died of pneumonia in 1918.

Though various legends have developed as to the inspiration for the poem, the most commonly held belief is that McCrae wrote “In Flanders Fields” on May 3, 1915, the day after presiding over the funeral and burial of his friend Lieutenant Alex Helmer, who had been killed during the Second Battle of Ypres. The poem was written as he sat upon the back of a medical field ambulance near an advance dressing post at Essex Farm, just north of Ypres. The poppy, which was a central feature of the poem, grew in great numbers in the spoiled earth of the battlefields and cemeteries of Flanders. McCrae later discarded the poem, but it was saved by a fellow officer and sent in to Punch magazine, which published it later that year.

In Flanders fields

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Doughboys

Posted on August 1, 2014 Leave a Comment

I became obsessed with WWI in the fall of 2011. A new bakery and coffee shop called Doughboy opened in the West Village. It was at the corner of Charles and Hudson streets. Not only was it a refreshing alternative to Starbucks, they made the best banana bread I’ve tasted since my grandmother died in 1982.

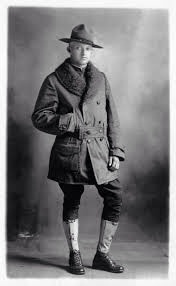

Doughboy became my Saturday afternoon destination spot. I’d meet friends there for coffee and a slice of their delicious banana bread. On the walls of Doughboy were the most amazing photographs of WWI soldiers. The warm sepia toned photos gave life to a generation of men that had long been forgotten. But, it was their uniforms that got me. Those boys had a look – and of course, I’m always on the prowl for a new look.

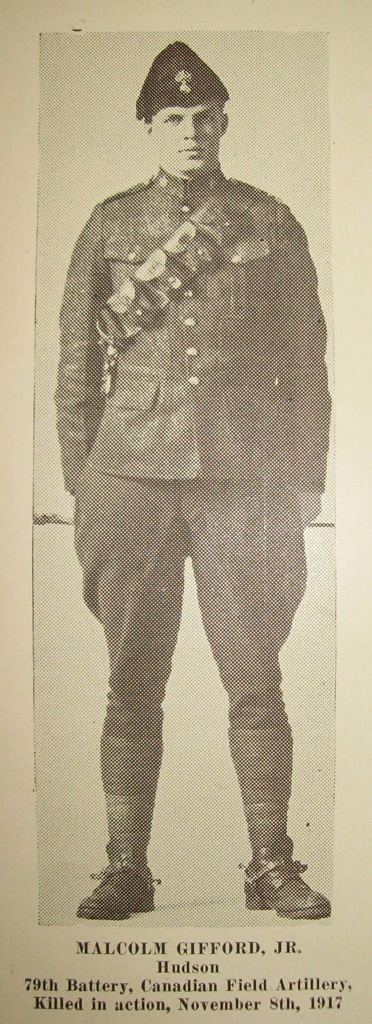

Then one day while researching WWI uniforms, I stumbled across a picture of a young man named Malcolm Gifford Jr. Suddenly my whole childhood came pouring back to me. Mr. Gifford was the ghost in Grandma’s attic. I needed to find out more about his story. So, off on I went like a modern day ghostbuster…

Over There

Posted on July 31, 2014 Leave a Comment

“Over There” is a 1917 song popular with United States soldiers in both world wars. It was a “propaganda” song designed to galvanize American young men to enlist in the army and fight the “Hun”.

It was written by George M. Cohan in April 1917. Americans believed at that time that the war would be short and the song reflected that expectation.

Notable early recordings include versions by Nora Bayes, Enrico Caruso, Billy Murray, Arthur Fields and Charles King. According to Michael Duffy of FirstWorldWar.com, “Cohan later recalled that the words and music to the song came to him while travelling by train from New Rochelle to New York shortly after the U.S. had declared war against Germany in April 1917.”

By the time “Over There” was released, Malcolm was already over there. In February 1917, two months before the United States entered World War I, He and some fellow students from Williams College travelled to Montreal and enlisted in the Canadian Army. He served as a Gunner in a feld artillary unit.

If you could read my mind

Posted on July 30, 2014 Leave a Comment

My new book is a love letter to the ghost in my grandparent’s attic. It was inspired by Gordon Lightfoot’s 1971 song If You Could Read my Mind. I can’t wait to share it with you soon.

If you could read my mind, love

What a tale my thoughts could tell

Just like an old-time movie

‘Bout a ghost from a wishin’ well

In a castle dark or a fortress strong

With chains upon my feet

You know that ghost is me

And I will never be set free

As long as I’m a ghost that you can’t see

If I could read your mind, love

What a tale your thoughts could tell

Just like a paperback novel

The kind the drugstores sell

When you reach the part where the heartaches come

The hero would be me

But heroes often fail

And you won’t read that book again

Because the ending’s just too hard to take

I’d walk away like a movie star

Who gets burned in a three-way script

Enter number two

A movie queen to play the scene

Of bringing all the good things out in me

But for now love, let’s be real

I never thought I could act this way

And I’ve got to say that I just don’t get it

I don’t know where we went wrong

But the feeling’s gone and I just can’t get it back

If you could read my mind, love

What a tale my thoughts could tell

Just like an old-time movie

‘Bout a ghost from a wishin’ well

In a castle dark or a fortress strong

With chains upon my feet

But stories always end

And if you read between the lines

You’ll know that I’m just tryin’ to understand

The feelings that you lack

I never thought I could feel this way

And I’ve got to say that I just don’t get it

I don’t know where we went wrong

But the feeling’s gone and I just can’t get it back

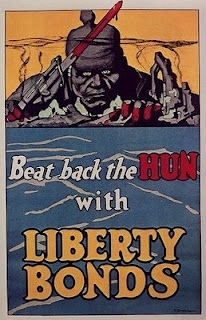

Beat Back The Hun

Posted on July 29, 2014 Leave a Comment

I’ve tried my whole life to understand Grandma’s perfectionism. She had a deep seated need to control her entire world. What happened to her that caused those dark moods? There were times when we sat at the Steinway, and I was having trouble with a particular piece, she was so loving and gentle. Then other times, on those dark days, she would turn on me. I knew it must have had something to do with her German ancestry. But, she never told me the stories of what it was like to grow up during World War I as a German American. It must have been horrible.

During World War I, German Americans were often accused of being too sympathetic to Germany. Former president Theodore Roosevelt denounced “hyphenated Americanism”, insisting that dual loyalties were impossible in wartime. A small minority came out for Germany, or ridiculed the British (as did H. L. Mencken). Similarly, Harvard psychology professor Hugo Münsterberg dropped his efforts to mediate between America and Germany, and threw his efforts behind the German cause.

The Justice Department attempted to prepare a list of all German aliens, counting approximately 480,000 of them, more than 4,000 of whom were imprisoned in 1917-18. The allegations included spying for Germany, or endorsing the German war effort. Thousands were forced to buy war bonds to show their loyalty. The Red Cross barred individuals with German last names from joining in fear of sabotage. One person was killed by a mob; in Collinsville, Illinois, German-born Robert Prager was dragged from jail as a suspected spy and lynched.

When the United States entered the war in 1917, some German Americans were looked upon with suspicion and attacked regarding their loyalty. Some aliens were convicted and imprisoned on charges of sedition, for refusing to swear allegiance to the United States war effort.

What kind of an American are you?

Posted on July 29, 2014 Leave a Comment

As the first draftees appeared at their inductions in 1917, the nation’s lyricists were already questioning the loyalty of the immigrants. “What Kind of An American Are You?” starts with a conciliatory tone, but turns brazen and demanding. “This land of the free,” we and they are assured, “is for you and for me. / Or for anyone at all who is seeking liberty. / We welcome every stranger and we help him all we can.” The open hand of friendship and aid is not a new ploy for these writers and, of course, there is a “gotcha.” “And now that we’re in danger,” the trap begins to close, “we depend on every man.” The same demand for loyalty and gratitude that is the prevailing oeuvre of these songs, comes to the fore again. “The Stars and Stripes are calling you to lend a helping hand,” as one good deed demands reciprocation, and “If you’re true blue, it’s up to you to show just where you stand.” Loyalty, unlike faith, depends on acts and appearances—especially under the Espionage Act. The refrain is a “Put up or shut up” and “Love it or leave it” all concentrated in one passage.

More…

The First Supermodel

Posted on July 29, 2014 1 Comment

In the early part of the 20th century, the figure and face of Evelyn Nesbit was everywhere, appearing in mass circulation newspaper and magazine advertisements, on souvenir items and calendars, making her a cultural celebrity. Her career began in her early teens in Philadelphia and continued in New York, where she posed for a cadre of respected artists of the era, James Carroll Beckwith, Frederick S. Church, and notably Charles Dana Gibson, who idealized her as a “Gibson Girl.” She had the distinction of being an early “live model,” in an era when fashion photography as an advertising medium was just beginning its ascendancy.

More…

Sweet Baby James

Posted on July 28, 2014 Leave a Comment

After the trials, Malcolm graduated from Williston Academy and enrolled in nearby Williams College. The route from Amherst to Hudson was the final leg of all those roadtrips from Maine to Columbia County to visit Grandma and Grandpa. I knew the route like the back of my hand and could drive it in a blackout. The trouble was I didn’t have a car and no other way to get home for Thanksgiving that sophmore year. I was never a very good hitchhiker. My brother BJ was much more adventurous and far more succesful than I. He taught me the sign trick and showed me the way and said, “you never need to be stranded when you hitchhike.”

So, I whipped out a cardboard box and tore the flaps off and wrote the names of the most important landmarks of my pilgrimage – Springfield, Stockbridge, Mass Pike, Taconic PKWY, Hudson. I had no way of knowing that it would be the last time I’d see Grandma alive. I just knew I had to get home to Hudson, to sit at the Steinway, to sit in the oval shaped dining room, to give thanks with my family.

It seemed like hours had past as I sat on the guardrail on the off ramp of the Mass Pike watching the cars wizz by. Finally, a car slowed and the driver motioned for me to get in. “Where are you going son?” He asked. “Hudson.” I replied. “Well, today’s your lucky day kid. I’m headed there myself. We’ll be home before you know it.”

I sank into the passenger seat, relieved, and closed my eyes. On the radio, was playing James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James.

Poor Little Rich Girl

Posted on July 27, 2014 Leave a Comment

Viola Dana was born Virginia Flugrath on June 26, 1897 in Brooklyn, New York. Dana became a child star, appearing on the stage at the age of three. She read Shakespeare and particularly identified with the teenage Juliet and enjoyed a long run at the Hudson Theater in New York City. At the age of sixteen Dana was a particular favorite of audiences with her performance in David Belasco’s “Poor Little Rich Girl”. She went into vaudeville with Dustin Farnum in “The Little Rebel” and played a bit part in “The Model” by Augustus Thomas. Dana made her film debut in 1914 in “Molly the Drummer Boy” (1914). The following year she received top billing playing Gladiola Bain in “Gladiola” (1915). Dana secured another lead in “The Innocence of Ruth” (1916) and then starred in “The Girl Without a Soul” and “Blue Jeans” (both in 1917) for Metro Pictures Corporation. She continued to act throughout the 1920s with her most notable role coming in 1926 as Katie O’Doone in “Bred in Old Kentucky”. In the late 1920′s Dana’s popularity began to wane and her final silver screen role was in “One Splendid Hour” (1929) after which Dana retired from films.

More…